Tags

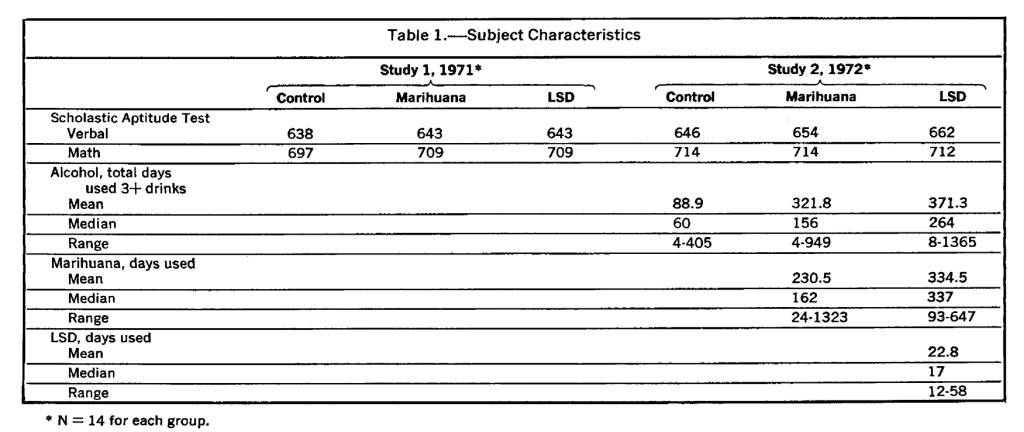

Long ago a person in the comment section told me about an excellent study in which several groups of Dartmouth seniors were administered the WAIS (Culver & King, 1974).

What made the study especially useful is their SAT scores (probably taken when they were around 17) were provided:

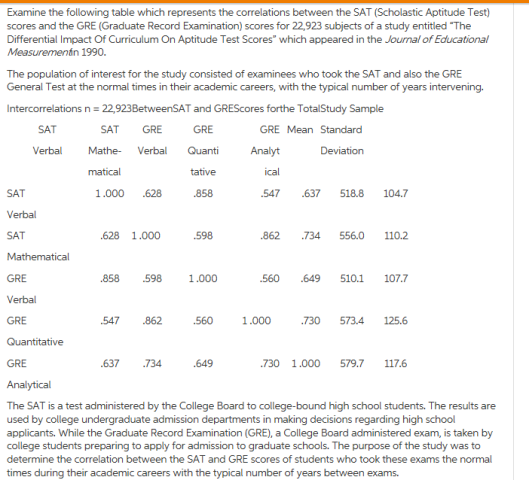

I decided to focus on the control groups because their IQs were least likely to be impaired by the substance abuse effects the study investigated. The 1971 Dartmouth control group averaged a combined SAT of 1335 and the 1972 control group averaged a combined SAT of 1360. Averaging these together gives 1348. Since the students were 20 to 25 when they took the WAIS in 1970 to 1972, they probably took the SAT from 1965 to 1969. Based on national norm studies I estimate that if virtually all American 17-year-olds took the SAT in 1960 and 1974, the mean and standard deviation (SD) would have been 784/210 and 770/204 respectively.

Since the WAIS was normed so that a representative sample of U.S. adults in each age group would have a mean IQ and SD of 100 and 15 respectively (see WAIS manual, chapter 2), I equated the national means and SDs of the SAT to 100 and 15 also. By this measure a 1360 on the SAT equated to an IQ of 141 or 143 depending on whether I used the 1960 or 1974 norms. Let’s split the difference and say 142. Meanwhile the full-scale WAIS IQ of the Dartmouth control group students was 129.

Now because they were tested circa 1971 and the WAIS was normed circa 1953.5, their scores are inflated by a 17.5 year Flynn effect. According to the brilliant and influential James Flynn (RIP), the Wechsler Flynn effect was 3 points per decade but according to my own independent research, it was more like 1 point a decade. Flynn (who was always kind enough to respond to emails) told me my research was not accurate because I was using a pre-war Wechsler scale and IQ tests did not become accurate until after WWII. I countered that his own research may be compromised by test order effects. (Davis 1977, Kaufman 2010)

Using Flynn’s estimate, their IQs need to be reduced to 124 but using mine they need to be reduced to 127. Either way, they scored substantially lower on the WAIS than they did on the SAT. This is to be expected because Dartmouth students were largely selected by SAT scores and given the imperfect correlation between standardized tests, people who are selected using one test should regress to the mean on another and assuming a bivariate normal distribution, the slope of the standardized regression is a function of the correlation between the tests.

So given an SAT that was 42 points above the U.S. mean defined as 100, the expected correlation (r) between the WAIS and the SAT is:

r = (number of IQ points above 100 on the WAIS/number of IQ points above 100 on the SAT)

r = (24 or 27/42)

r = 0.57 or 0.64

Let’s split the difference and say 0.61.

Because Herrnstein & Murray (1994) popularized the myth that Ivy League students have IQs in the stratosphere (and Jordan Peterson believed it, even though studies he co-wrote show otherwise) I was surprised to learn that at least one of The Bell Curve’s authors knew the truth, though this was relegated to the footnotes (see page 688):

[Update July 28, 2024: an earlier version of this article suggested the correlation between the SAT and the WAIS be adjusted for the time difference between the two administrations however it’s unclear if such a an adjustment is valid]